Roger McGuinn’s work has been so closely associated with Dylan’s that it comes as no surprise, but with all the excitement of an inevitable triumph, that the Rolling Thunder Revue has revived his career. By almost all accounts, McGuinn has been the most impressive of Dylan’s coperformers on the RTR tour. Cardiff Rose more than confirms that; it is McGuinn’s finest album since he disbanded the Byrds four years ago. He’s singing with conviction and passion again. These songs aren’t just chips haphazardly thrown into the pot to stem the ennui; they are used as they should be—to raise the stakes.

As Bud Scoppa has pointed out, McGuinn has always been a gifted team player who needs the collective support and tension of others to temper his self-indulgent and self-destructive impulses. In Dylan’s touring band, Guam, and with ex-Mott the Hoople and RTR stalwart Mick Ronson, the producer of Cardiff Rose, McGuinn has found the strongest and most stable unit he’s worked with since going solo. It is a central part of this album’s double vision—the déjà vu which it conveys—that Guam recalls the Byrds, although deliberately avoiding the latter’s trademark style. For like the Byrds, Guam is an oddly anonymous band (a result, no doubt, of backing a variety of RTR performers) whose most salient attribute is the totality of their sound. They play straightforward, hard-edged rock & roll with no frills or fat. Much of the credit must go to Ronson for providing McGuinn with a musical framework which is as cohesive as the Byrds and as muscular as Mott.

An extension of McGuinn’s need for a band has been his equally strong search for community. A strong case can be made for the parallel rise and fall of the Byrds’ career with the Sixties bohemian scene in Los Angeles, in which the Byrds performed a major role as musical spokesmen. The Rolling Thunder Revue, with its conscious attempt to re-create the Sixties folk scene in Seventies terms, has provided McGuinn with his first community, however insular it may be, since his early L.A. days. The album’s first cut, "Take MeAway," describes McGuinn’s exhilaration at being part of the revue:

You should’a been there

When time was right for the music to begin,

You should’a been there

When that band of gypsies started rollin’ in.

Amid all these references to the revue and the past, it is no coincidence that the centerpiece of Cardiff Rose is "Up to Me," a song that Dylan wrote in 1974 (presumably around the time of Blood on the Tracks) but never recorded. The album’s longest cut, it is the most explicit, least allegorical song that Dylan has written about his career ("If I’d thought about it/I never would’ve done it/I guess I would’a let it slide") and marriage ("She’s everything I need and love/But I can’t be swayed by that"). With its obscure allusions, charged imagery and machinegun lyrics, the song, like almost all of Dylan’s work, functions on a variety of levels, encompassing far more than simple autobiography. McGuinn’s accomplishment is that he claims the song with the same authority as he did with "Mr. Tambourine Man." Though he’s playing the same role as he did 12 years ago, not once does he sound like a stand-in.

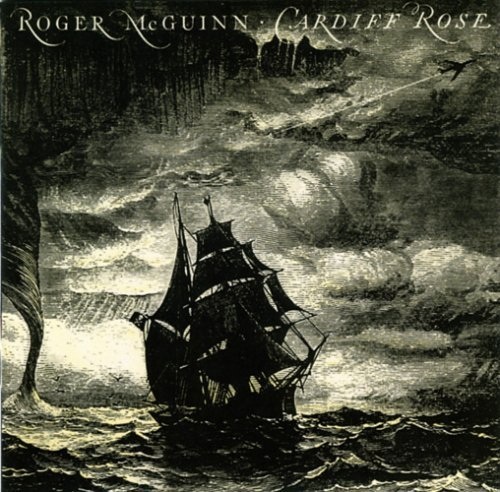

If "Up to Me" is the album’s keystone, anchoring Cardiff Rose in the world of rock & roll, "Jolly Roger" (the pun is intended) and "Round Table" are its mythological counterparts. Both songs are about self-sustaining groups—a band of pirates and King Arthur’s knights—whose existence revolves around violence. But it’s clear where McGuinn and colyricist Jacques Levy’s sympathies lie. The buccaneers do not justify their acts or deny the pleasure of taking spoils. The knights pillage in the name of Christianity. Though it may seem like a dubious moral distinction in post-Watergate Seventies, McGuinn appears to be differentiating between outlaws and criminals—a distinction that Levy and Dylan are unable to make in juxtaposing Hurricane Carter and Joey Gallo on Desire.

McGuinn and Levy are not nearly as successful, however, in "Partners in Crime," their maudlin ode to Abbie Hoffman. The song is an embarrassing tribute essentially to the vicarious thrills of radical chic. In similar fashion, McGuinn compares the life of a rock & roller to that of a criminal in "Rock and Roll Time," a song he cowrote several years ago. The ferociousness of his vocals almost saves the song from its own self-pity.

The two songs which recall McGuinn’s own past are "Friend" and "Pretty Polly." The former is both sentimental and crude, but it works precisely because of the intensity of McGuinn’s expression. He transforms "Pretty Polly," an innocuous traditional tune, into a grisly ballad of murder. The album closes with "Dreamland," an unrecorded Joni Mitchell song, which derives as much of its power from the music as it does from the lyrics—further proof that Mitchell’s songs are greatly enhanced by strong melodies and arrangements. "Dreamland" rocks with joy, bringing the album full circle.

Cardiff Rose is by no means an unflawed album. The premise that a rock & roller’s life is the same as a criminal’s is ultimately self-serving. But there is a sense that McGuinn, having found a new community in Rolling Thunder, is coming to terms with his career again. If his failure is that of overreaching, at least he hasn’t done that for years. (RS 217)

KIT RACHLIS