Here’s a review from a guy named Doug Collette on All About Jazz:

Serendipity is dead! Grateful Dead that is.

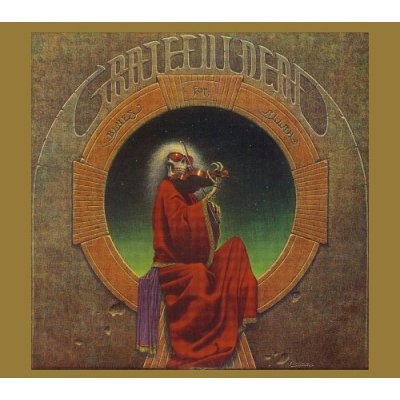

A successor to the similarly massive and comparably gorgeous box set The Golden Road (1965-1972) , Beyond Description (1973-1989) depicts the latter day Grateful Dead’s utter and perhaps naive willingness to surrender to their muse for inspiration, whether it be on the stage or in the studio. It becomes quite clear before you are even half-way through these dozen extended remastered CDs that, when this band was struck with inspiration, there was hardly one better. When they were not enlightened with ideas, either new or old, they were as nondescript as any anonymous bar band in the land.

And different things could inspire the Dead. With Wake of the Flood , it was no doubt the sense of creative freedom from the corporate business pressures of the major label (Warner Bros) they’d just left to begin their own career as an independent rival. Before the difficulties of that role set in, combined with the sieve-like drain on their resources presented by their self-designed wall of sound system for the road, the misrouted trip to the Egyptian pyramids and the naive dive into movie making, the collective spirit of ingenuity gave birth to Blues for Allah , without a doubt the finest studio rendition of Grateful Dead improvisation ever to be captured on tape without a paying audience.

Their existence in the recording studio had its positive and negative effect on the band throughout its career right up til the end. Guitarist/songwriter Jerry Garcia’s idea to have the band play ‘live’ for In the Dark was counterpointed by the layered approach of Built to Last where individuals composed their parts only to be assembled after the fact. That’s sort of like taking the Swiss watch apart then putting it back to together again, but at least there was a theme to the fundamental ideas behind those sessions: Shakedown Street , for all its good material—at least four cuts from this album became live staples—suffers terribly for an almost absentminded lack of focus.

Given the ingenuous nature of this band, it’s perhaps little surprise that one of their most pure instances of inspiration—Garcia and lyricist Robert Hunter’s near-simultaneous creative epiphany giving birth to “Terrapin Station”—would end up one of their most seriously tainted projects. For this, their first record for Arista—founded by the archetypal record mogul Clive Davis as an expatriate of behemoth Columbia Records—Grateful Dead deferred to producer Keith Olsen, fresh off his mammoth success with Fleetwood Mac, who orchestrated stings and vocal choir for this epic piece; a tighter more concise arrangement, emphasizing the spaces between the pieces of the suite rather than filling those spaces, would’ve been much preferable. The melodrama on the studio version is almost laughable, especially given what the band, even so recently as this summer, was able to do with the piece in concert, and the fact that melodrama is virtually alien to this group that brought new meaning to the word understatement.

Digesting the expanded versions of these studio efforts reveals just how the Grateful Dead’s idiosyncratic nature wasn’t refused free reign by the likes of then-hot producers such as Gary Lyons (Foreigner, Aerosmith). His cookie-cutter approach on Go to Heaven renders the band’s amorphous essence virtually indecipherable on the album as originally released, but then the Dead didn’t do much to make themselves a more pronounced factor in the proceedings: Bob Weir could be the essence of convention and new recruit Brent Mydland, despite the vocals and varied keyboard work that added contemporary colors to the collective palette, only added to the general sense of anonymity. But as astutely noted in the album summary, the live versions of “Althea,” one of a pair of Garcia/Hunter compositions on the album, plus the natural pairing of Weir’s “Lost Sailor” and “Saint of Circumstance,” reveal the Dead hadn’t lost their essential character—it’d been simply lost in the process of producing the album. The same revelation arises from the studio outtakes such as “Peggy-O:” Lyons’ unsympathetic tweaking of the recorded sound lost the drums interplay and the resounding drive and ingenuity of Lesh’s basswork.

Little wonder given such less-than-satisfactory incidents the Dead felt more comfortable playing on a stage in front of an audience than in a recording studio, even if the environment had been contrived for their own benefit (Garcia conceived Workingman’s Dead with an angle to economics of musicianship as well as studio costs, with the pithy approach of Buck Owens’s Bakersfield CA country music as a template). And all this is not to suggest that these San Francisco icons had any more difficulty in the studio than many other artists, improvisationally-oriented or not:their 1986 touring partner/peer Bob Dylan has been at least as lackadaisical as the Dead, if not more so. Certainly, though, to listen to the two-double disc expanded live albums included in this ornately- designed box set is to understand Grateful Dead benefited from the mutual camaraderie of each other and their audience in front of the stage more than most, if not all, rock and roll bands.

Such an obviously high comfort level allowed them to stage the multi-night runs in California and New York in 1980 that make up Reckoning and Dead Set. The former is a compilation of the acoustic sets played as openers for those shows, an understated but hardly less amazing amalgam of originals and roots of their folk/country/bluegrass originals.

This may be the sleeper of this collection, aptly described by essayist Gary Lambert (with the perceptive objectivity and obvious affection that also earmarks long-time publicist Dennis McNally’s history of the band as well as the other individual stories behind the albums) as a collection of Dead originals that naturally lent themselves to the folkish treatment [”Dire Wolf”], staples of the band’s electric configuration [”Cassidy”] that translated into superb acoustic jamming vehicles, some never to be repeated rarities [”Rosalie McFall”], and a bunch of well-chosen covers [”The Race Is On”].” Certainly the mix of acoustic guitars, enriched by Bill Kretutzmann and Mickey Hart percussion compares favorably with the Dead’s rock alignment, especially when accented by keyboardist Brent Mydland with the unconventional spirit he brought to the Dead—harpsichord on “Dark Hollow” is a starling yet appropriate change of pace from the acoustic piano that underscores the traditional feel of these sets.

And the band plays with equal amounts economy and exploratory zeal, throughout the two extended discs, offering more insight and more music than the original lp issue. Those characteristics mirror the jaunty approach of the electric companion piece Dead Set. The full-speed ahead propulsion in Phil Lesh’s great rocker “Passenger” is offset, proportionately, by the stillness of “Row Jimmy.”

In direct dynamic contrast to their brethren The Allman Brothers Band, who utilize the simplicity of the blues to connect directly to polar emotions of agony and ecstasy, The Dead’s wider influences virtually guarantee a mix of emotions as well as a roundabout means of reaching them and, in turn, expressing them, to their listeners. It’s the difference between pastel shades and bolder strokes of deeper color.

Whatever their miscues in the recording studio, it’s a tribute to Grateful Dead’s integrity they did not compromise themselves on stage and the live selections throughout this collection confirm that, generally speaking, it’s fascinating to follow one of their group improvisations even if it doesn’t lead to a truly galvanizing moment, the likes of which their legend is built. Not every truly great conversation, musical or otherwise, necessarily leads to an epiphany.

It’s to the credit of the producers of Beyond Description , David Lemieux and James Austin that, in particular with these live albums, they made no attempt to re-create them, but simply add on to them (besides, how do you create an alternate version of an alternate universe, which is what Grateful Dead music signified, at both its high and low points?). Yet it’s a matter of practicality too, because the bulk of the bonus tracks on the studio CDs are concert cuts rather than sterling alternate studio takes or unreleased recordings that would conceivably reinvent the original. This selection of albums may not compare with those in the previously-released box, including American Beauty and Europe ’72 , but the fact of the matter is, the deep, crystalline sound quality bestowed upon these recordings through HDCD remastering—by Joe Gastwirt whose name in credits almost guarantees great sound— makes the music worth hearing, despite its erratic nature, from disc to disc and sometimes, as in Wake of the Flood , from track to track. And it’s no coincidence that, even when it’s a curiosity like Lowell George singing “Dancing in the Street,” the extra tracks are superior to most of those included in the prior box. And how great is hindsight: after three successive duds overseen by commercial producers, the Dead scored their ‘hit’ supervising themselves in the studio!?

The distinction of the live package Reckoning as presented in Beyond Description might not have been so clear except in retrospect. Take the well of influences shared by the members of the band: as broad as it was deep, Bob Weir, contrary to his perpetually boyish persona, knew jug- band music arguably as intimately as Garcia, who was asked to join the former’s band pre-electric Dead! It’s little surprise, either, that the marathon sets of five-hours plus from which these recordings are taken derive much of their impact from the cumulative effect of the sets. Just as some of the sequencing on Dead Set does little to generate continuity—you contend it actually disrupts the momentum, such as it is—it likewise illuminates the source of the catchphrase of the times “there (was) nothing like a Grateful Dead concert.”

Up until the band hit the mainstream so resoundingly with “Touch of Grey,” their self-generated community created a culture within a culture, where few if any of the rules generally accepted by society were in effect. If you accept this phenomenon as a direct outgrowth of the band’s own laisezz faire ethos, where they open up to their muse rather than chasing it, then you understand instinctively how the music took something of a downturn as the Dead’s audience grew to include many for whom the music was not of primary importance: the immediate feedback of the audience was lessened (might this explain the Dead’s resurgence in interest toward the studio?).

Like a scrapbook assembled with loving care, the two booklets included in the box, brimming with photos, information and insight (not to mention timeless memorabilia), offer an accurate subtext to a tale told with picturesque detail and a joyful sense of adventure in both the songs and the playing of them. Yet the most practical value of Beyond Description (1973-1989) is its focus on a phase of the Grateful Dead’s existence that is as often misperceived as it is overlooked. For instance, the early studio albums that are part of this set, especially From the Mars Hotel , should benefit tremendously from a rethink and, ultimately, these unsung facets of the group’s existence deserve this lovingly-detailed, scholarly-researched, high-tech documenting. None of us, archivists, casual listeners or devout Deadheads, should fool ourselves into thinking we’ve definitively captured the Grateful Dead here, but as chief archivist Lemieux suggests ever so forcefully in his general introduction, as the Dead’s legacy continues a veritable work-in-progress. their music remains a living breathing entity.

Visit the Grateful Dead on the web.