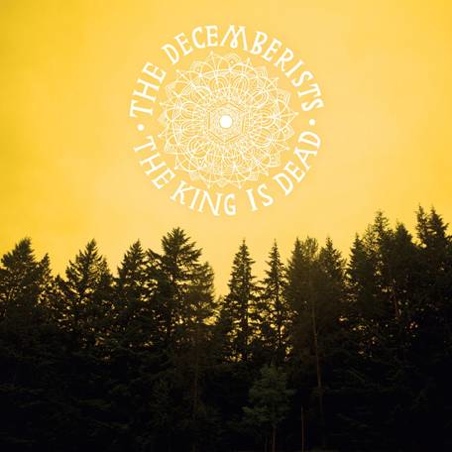

Having tired of the sprawling magnificence of their two last albums,The Decemberists have thrown out convolution in favour of conciseness. Band leader Colin Meloy wanted music to play live that didn’t need to be framed by other songs, tunes that could just be busted out. Enter The King Is Dead. Produced by 2009 album The Hazards Of Love’s Tucker Martine, guests include Peter Buck and Gillian Welch whose hefty contribution underlines the album’s Americana influences and direction. It’s been billed as an organic, unpretentious batch of country-tinged tracks recorded in a converted rural Oregon barn over a bucolic summer. The $165 Deluxe Box Edition comes with a selection from the over 2500 Polaroid pictures of the band taken during the recording sessions. It’s all so tasteful and stylish and god damn coffee table. I imagine hardcore fans will be weeping with anticipation.

There are less English influences here and an obvious push towards Americana; a swing back across the Atlantic, echoing the band’s move back towards the unfussiness of early albums. Although these aspects of The King Is Dead aren’t hugely pronounced, they are vast considering The Decemberists’ consistent English folk influences of previous work. But if they said they’d recorded the album in Ireland, I’d have believed them – it’s often more mid-nineties crusty-folk bandThe Levellers than mid-seventies Neil Young. The violins can become a bit fiddle-de-dee, veering from drunken barn-dance honky-tonk to Irish shindig and occasionally a bit too mid-tempo and plodding. But there are some grand, soaring moments, some Darkness On The Edge of Town rip-roaring harmonicas and chiming guitars courtesy of Peter Buck (R.E.M. is an obvious cornerstone of the album’s sound). I’m a sucker for slide guitar and they heap it on. This possibly covers up blemishes like a stick of audio cover-up but still, as I said, I’m a sucker for slide guitar.

There is enough of a dynamic range across the album to make it an attractive listen. Slow, stately country-folk songs sit pretty alongside the mid-tempo plodders. It does feel strange to hear Colin Meloy singing lyrics that aren’t caught up inside a grander narrative, but often the quality of the tracks are good enough to erase any doubts about the leaner, simplified direction. Meloy claims it was harder to write these shorter songs than his sprawling concept albums, and on this evidence he could be half-right. The problem could be in making the songs interesting enough to stand-alone. But they pull it off, illustrating that a concise approach need not detract from meaning and emotion.

The King Is Dead is the sum of its inspirations; an attempt to be more concise inside a country-folk framework, and it might just be the album to take them into the heart of the mainstream.