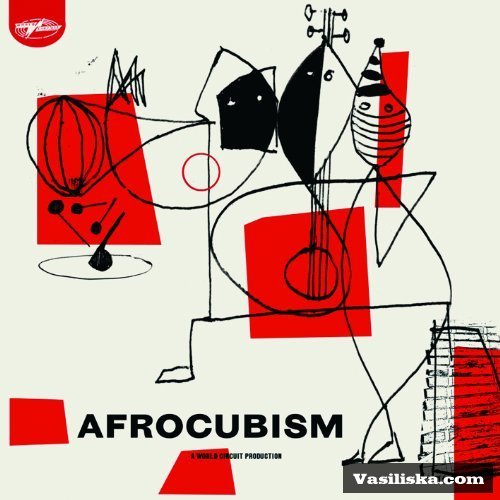

AfroCubism: AfroCubism

By Russ Slater 29 November 2010

Africa meets Cuba on the Malian Social Club that almost never was…

In 1996, Nick Gold, head of World Circuit Records, invited Ry Cooder to record a collaboration between musicians from Cuba and Mali in Havana. Cooder arrived in Cuba, but the Malians never did (something to do with their visas), and the project morphed into the Buena Vista Social Club: a film, tour, and, most importantly, a record. The album sold five million copies, won a Grammy award, and became the prototype for any record company with ambitions of selling world music. The Malians have no doubt been kicking themselves ever since.

Now, 14 years later, the musicians from West Africa finally get their chance. While it’s never going to equal the success of Buena Vista (the circumstances behind that record’s fruition are too impossible to match), it offers the opportunity to hear what may seem, on paper, a very strange idea. In fact, the link between Mali and Cuba is extremely strong. Following independence from France in 1960, Mali’s President Modibo Keita introduced One-Party Socialism, becoming friends with Fidel Castro in the process. During Keita’s reign, Cuban music was actively promoted throughout the country. As a result, many Malian musicians are now as comfortable at playing son and rumba rhythms as their own.

Afrocubism should then offer a perfect union between these two groups of musicians. Unfortunately, despite some real successes, this is not completely achieved. It’s apparent which of the songs are written by Malians and which by Cubans, and not because of the different languages they’re singing. From a fusion perspective, the most interesting are those with Cuban rhythms, such as the opening two tracks, which both start off sounding like the brothers of Buena Vista before allowing for the Africans to move within their grooves. This is where it gets really interesting as we get to hear Toumani Diabaté playing the kora, a 21-string musical harp, Lassona Diabaté on the balafons, sounding somewhere between a xylophone and marimba, and Djelimady Tounkaru playing the guitar in his own inimitable style.

The contrast between the rustic voice of Eliades Ochoa, leading the Cubans on this album, and the rhythmic tones of the African instruments is delightful, and it is successful all over the album, as “A La Luna Yo Me Voy” and “Para Los Pinares Se Va Montoro” demonstrate later on. There always seems to be enough room in the songs for the Malians to add their inflections and licks, giving the songs extra gravitas and ebb than they would have otherwise.

Although the Malian musicians were well aware of Cuban music, it’s possible that the opposite may not be true. This would certainly explain the lack of Cuban flavour on some of the African tracks. Whereas on the songs of Cuban origins, the Malians manage to get over their identity; this never quite happens when the shoe is on the other foot. Cuban flavour throughout Afrocubism is represented by Ochoa on guitar and vocals, and various other musicians playing percussion and horns, yet when the songs are not in Spanish, their presence is largely unfelt. “Jarabi” is a perfect example. The song, written by Toumani Diabaté, is the centrepiece of the album. Its pulsating rhythm, composed of balafons, kora, and minimal percussion, features the stirring vocals of Kasse Mady Diabate, and brings to mind Youssou N’Dour at his best. Apart from a shaker, it has little to no Cuban influence, which shouldn’t be an issue as I will listen to the song over and over again, but it does somehow take a little away from the aim of the album. It would have been great to have heard some Cuban guitar playing over African rhythms, but for whatever reason, Ochoas never seems to have the confidence to go down that route.

It’s for this reason that this album never quite reaches the goals it set for itself. We get to hear how terrific a number of these African musicians are and how easily they are able to blend their sound into Cuban rhythms, yet we never get to see this in reverse, which is a massive shame. It means that a musical journey which could have been quite groundbreaking has resulted in an album of two halves, of great music from Mali, and of great Malian musicians playing Cuban music. It’s still worth listening to as the music is of such high quality, but as a glimpse into something different, it keeps its eyes firmly shut.