If you want to make a great record, go to the top. That was what Bill Wilson figured anyway, which is why the 26 year old was knocking on the front door of Bob Johnston’s home in Austin. The feted producer of Bob Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel and Leonard Cohen had recently relocated to the Texan music town after falling out with Columbia records, from whom, he claimed, he had received no royalties for the stellar abums he had delivered.

Wilson had been kicking around Austin since being discharged from the U.S. Airforce three years earlier. Born in small town Indiana, Wilson had served in Vietnam before completing his duty to Uncle Sam at Austin’s airbase (these days a civilian aiport). As an aspiring musician he had tasted a little success, singing on a 1970 album by local psych-bluesers Mariani, who featured a 16 year old guitarist – and future star – Eric Johnson. After that Wilson had returned to Indiana to play dobro with an outfit called Pleasant Street.

Still, Wilson had never lost faith in his talent. He had a bunch of fine songs and Bob Johnston was surely the man to turn them into a record. Johnston had other ideas. “You came to the wrong house,” he snapped. “You can’t just show up and make a fucking record.”

“Will you listen to one song?” wheedled Wilson.

In his parlour, Johnson listened to a dozen. Impressed, he decided to cut an album that very night. He summoned a slew of top session players: guitarists Charlie Daniels and Pete Drake, pianist Bob Wilson, drummer Kenny Buttrey, steel guitarist Pete Drake – pretty much the Nashville crew he had used on Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde sessions, with singer Cissy Houston as a bonus. Then they went to work.

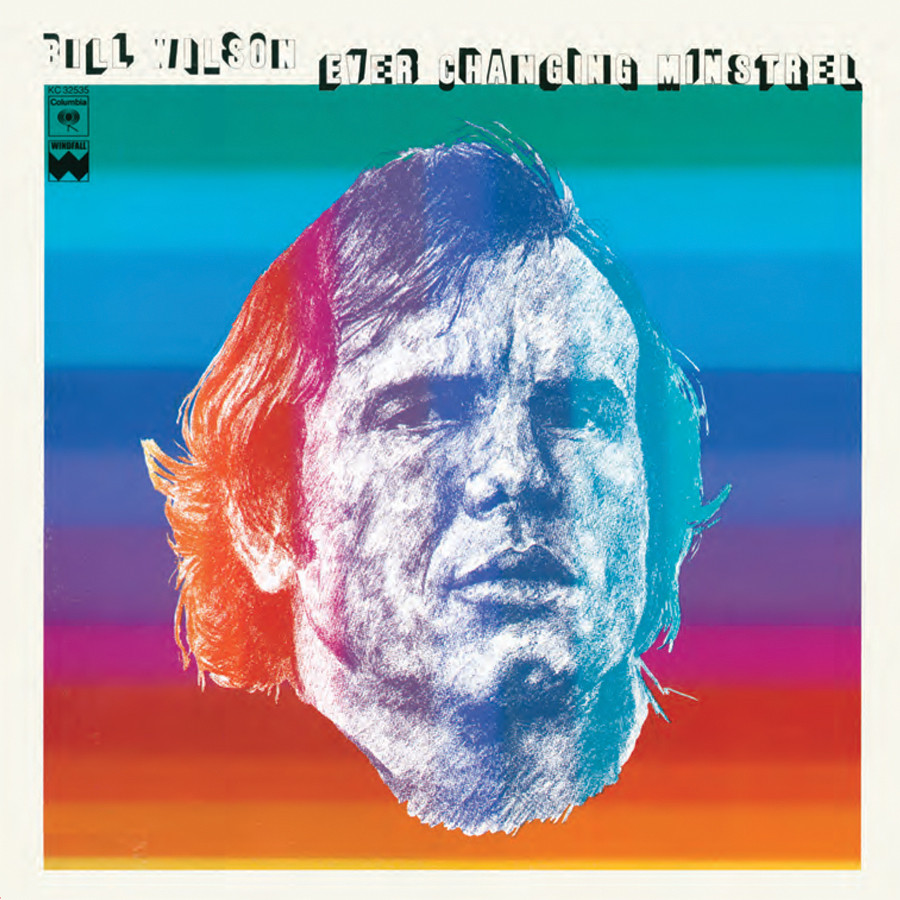

The resulting album was released in late 1973 on Windfall Records, a label distributed by CBS, though not, it transpired, with much ardour. Its hideous packaging likely didn’t help. Ever Changing Minstrel sank without trace. Its current re-emergence is down to happenstance, after Tompkins Square founder Josh Rosenthal found a copy for 25 cents in a Berkeley record store and noticed Johnston’s credit.

Both Rosenthal and Johnston had sound instincts. Ever Changing Minstrel is a collection of tough and tender pieces, the best of which bear the imprint of the early Seventies Austin scene of Guy Clark, and Townes Van Zandt. Wilson turns his rich tenor voice in various directions. “Black Cat Blues” has a southern, swampy feel akin to Tony Joe White’s “Polk Salad Annie” while “Ballad of Cody” is a cameo of a lonesome guitar picker along the rain-soaked streets of San Antone.

“Rainy Day Resolution” and “To Rebecca” are brighter pieces that walk singer-songwriterdom’s well-trodden avenues, with “Ever Changing Minstrel” crossing the line into a John Denveresque world of sleepy-eyed women, dripping rainbows, and bright meadows. It’s the only track set solely to picked acoustic guitar. Elsewhere those famous session men cut their stuff. “Long Gone Lady” – testament to Wilson’s fragile marriage – has some purring steel, “Good Ship Society” builds to a Band-esque ensemble piece, and “Following My Lord” and “Father Let Your Light Shine Down” come gospel-soaked, with hammered piano and female backing vocals. Religion clearly had its hold, though when Wilson starts a line “Caught between the devil” you don’t expect him to conclude “and the galaxy”. These were still hippie times.

If the album doesn’t add to more than the sum of its parts, there’s an engaging spirit to the session. Presented with his shot at the brass ring, Wilson didn’t fluff his lines or his notes. It must have hurt to see his album vanish into the corporate machinery. Vanish it did – Rosenthal could find no mention of the sessions or personnel in the archives, though Johnston recalls making it well enough. Wilson returned to Indiana and local hero status, gigging and recording until his death at 46, though Johnston never saw him again. The producer handed him a nice epitaph, though: “The fucker could really write”.

Neil Spencer, UNCUT