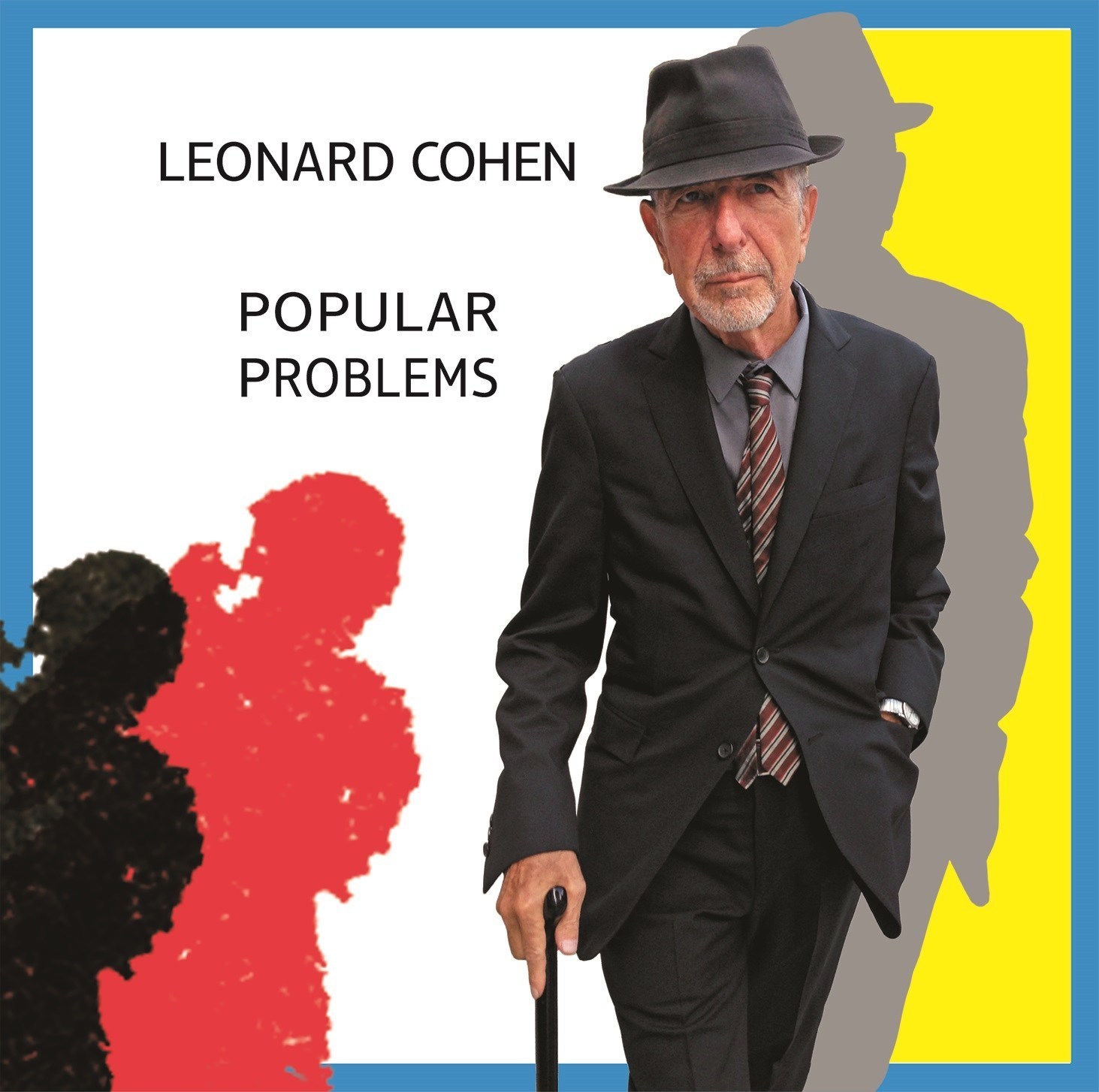

Leonard Cohen

Popular Problems

Columbia; 2014

By Mike Powell; September 24, 2014

7.6

The story of latter-day Leonard Cohen is one of wry acceptance. Fleeced by a manager of his retirement savings between the mid-1990s and mid-’00s, he returned to the stage in 2008, 73 years old and nearly broke after four decades of hard work. The shows he played were better than they needed to be in order to get people to pay for them. At one that I saw in late 2012, he reminded me of a cat, drawing the audience in by pulling away, rolling over and showing his softer, playful side only to snap back into cool focus. It was the first time I had ever seen anyone over 70 skip, and in dress pants, no less.

Come to think of it, it’s the kind of story you might hear in a Leonard Cohen song: the aging entertainer forced into the spotlight one last time just to make they money he’s already earned, a cog in the same machine that once made him a star. “It’s their ways to detain, their ways to disgrace,” goes a line from 1974’s “A Singer Must Die”. “Their knee in your balls and their fist in your face/ Yes, and long live the state, by whoever it’s made/ Sir, I didn’t see nothing, I was just getting home late.” In other words, “broke” is all the thanks most singers get.

Popular Problems is Cohen’s second album in the past two years. As with the 2012 LP Old Ideas, its best songs feel naked and hymn-like but are restrained by an underlying mystery—he sounds like he’s telling you everything but he never actually tips his hand. The flat airhorn of a voice he used throughout the ’70s has become eerily bottomless, the husk of another voice now gone.

Cohen is still an impossibly cool figure, singing about states of yearning and distress with the confidence of someone who knows that they—like everything—will pass. Even when he sings in the first person, he is heatless, as though watching his own failures from a distant star. “Did I ever love you?” he asks at one point. “Does it really matter?” The music behind him is a strange, sterile take on country—a form known for its certainty and wisdom, repurposed for a meditation on doubt.

Like all of Cohen’s albums, Popular Problems sounds slick but slightly off-kilter, like someone trying to imitate music they’ve read about but never actually heard. Where an artist like Bob Dylan seemed to use music primarily as an excuse for words and Van Morrison seemed distinctly to be the leader of a band, Cohen occupies a stranger space. His music over the years has been even more exploratory than his writing, changing style with the detached irreverence of a teenager breezing through her closet, from folk to lounge to ersatz disco and cabaret. The reminder here is that no matter how close Cohen seems to the truth, what he does is just another cheap show to keep the crowd entertained. Even in its starkest, most naturalistic moments, Popular Problems cannot—and does not want to—spare you its arsenal of perfect background singers and trumpets made of computer sounds.

Cohen has always had a remarkable way of making sadness sound triumphant and triumph sound sad. In a 2002 interview with Spin, he related a lesson he learned during his years studying Zen. “Roshi said something nice to me one time,” he started. “He said that the older you get, the lonelier you become, and the deeper the love you need. Which means that this hero that you’re trying to maintain as the central figure in the drama of your life—this hero is not enjoying the life of a hero. You’re exerting a tremendous maintenance to keep this heroic stance available to you, and the hero is suffering defeat after defeat. And they’re not heroic defeats; they’re ignoble defeats. Finally, one day you say, ‘Let him die—I can’t invest any more in this heroic position.'” The best songs here—”Samson in New Orleans,” “Born in Chains”—occupy that space: weary but optimistic, suffering but renewed.

Because Cohen is a thoughtful person on the edge of his 80th birthday, everyone seems to want to ask him about dying. “Naturally those questions arise,” he said in a 2012 press conference. “But, you know, I like to do it with a beat.” Which implies that his answers might be simple, but they aren’t. “There is no God in heaven/ And there is no Hell below” goes the last verse of a song on Popular Problems called “Almost Like the Blues”. “So says the great professor of all there is to know/ But I’ve had the invitation that a sinner can’t refuse/ And it’s almost like salvation; it’s almost like the blues.”

The idea being that heaven and hell are the same thing and you don’t even have to leave earth to get there. A compelling thought, but nothing to pray on. And yet the performance is so contemplative and so certain. Maybe it’s the Zen, which posits that change is permanent and our only choice is to accept the moment or become just another tragedy trying to force our way uphill. Half the time, it doesn’t even feel like Cohen is singing songs—he’s too busy with notes.

1. Slow

2. Almost Like The Blues

3. Samson In New Orleans

4. A Street

5. Did I Ever Love You

6. My Oh My

7. Nevermind

8. Born In Chains

9. You Got Me Singing