BOOKLET

here is the NFO file

released on Dust-To-Digital but includes the tracks from his Takoma release (Clearinghouse), which is one of my favorite releases from that label.

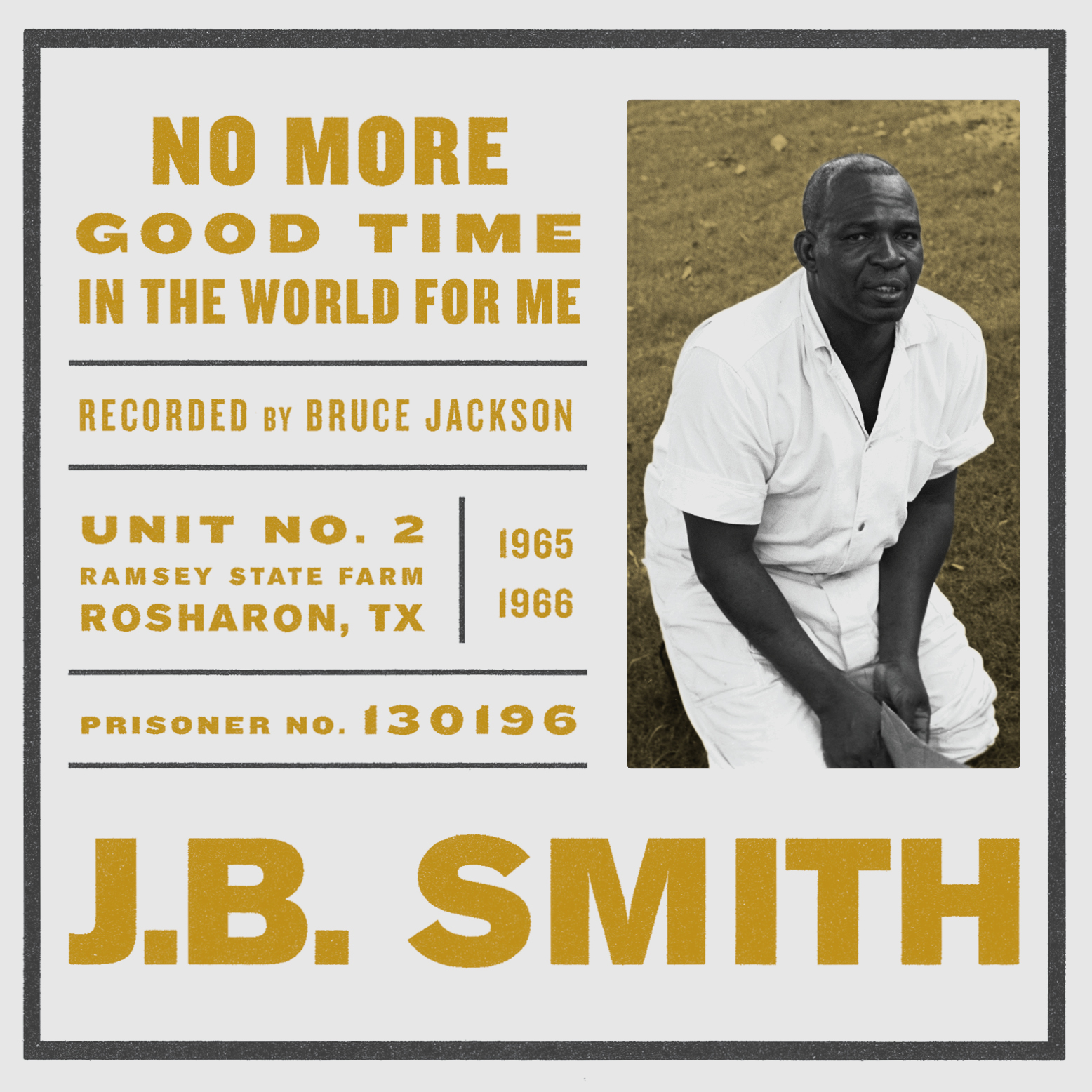

“50 years ago, archivist Bruce Jackson first went to Ramsey State Farm in Rosharon, Texas, to record the unaccompanied songs of J.B. Smith, an inmate serving 45 years there for the murder of his wife. He returned the following June in 1966 to record more, and that year John Fahey’s Takoma Records released an LP, Ever Since I Have Been a Man Full Grown, featuring three of Smith’s songs. “That album came out only because John Fahey had a lot of imagination,” says Jackson, who’d go on to author the definitive book on the subject of prison songs, Wake Up Dead Man. “To put out a record with just three unaccompanied songs and a little talk on it took a lot of balls.” Certainly, the Takoma record was released due to Fahey’s passion, but No More Good Time in the World for Me, a new two-disc set from Atlanta’s Dust-to-Digital, presents a fuller view of Jackson’s recordings of Smith, the three featured on the original LP and 15 more. Produced by Alan Lomax Archive curator Nathan Salsburg and Lance Ledbetter, the collection presents Smith’s songs as one long reading, which sprawls across an incredible range, with Smith singing of anger, sadness, toil, murder, and redemption.

“As a composition [“Ever Since I Was a Man Full Grown”] is discrete, it has integrity,” Salsburg says. “J.B. Smith was kind of an epic composer, in an extremely limited and debased setting. In prisons like Ramsey, Parchman, Angola, the goal was to dehumanize you, to make you fucking miserable. And the fact that the guy did what he did [in that place] and did it so beautifully, with such coherence and vision of content and characters and all that is remarkable.”

Along with Lomax, Jackson was among the last folklorists to record work songs — or time songs, for keeping time and passing it — like the ones Smith sang. “During the time I was working they started integrating the prisons,” Jackson says. “Once they integrated, the songs died entirely, because the white guys couldn’t do it, and a lot of the younger black guys thought it was old-timey stuff. It was sort of like capitulating to the white man. If I’d been five years later, I wouldn’t have gotten it.”

Beyond providing a rhythm for working convicts, so one worker’s pace wouldn’t be slower than another’s, which could lead to punishment, the songs offered a chance for expression. “You couldn’t say to somebody ‘I miss my old lady,’ or ‘I miss being able to walk down the street,’” Jackson says. “The other guy would look at you and go, ‘No shit, me too.’ But you could put it in a song and sing about it, just as you could put it in the blues on the outside.”

Smith’s songs were among the most expressive Jackson ever recorded. “His basic format is what is rhetorically called hyperbata,” Jackson says. “Normally in a blues, you get a line, the line will get repeated more or less the same, and then there’ll be a line that comments on that first line. What Smith does is he sings a line, sings a different line, repeats that line, and then sings the first again. The second line comments on the first, you hear it again, and the first line comments on the second line. It makes for a much more complex interplay of text. One verse doesn’t necessarily follow the other in a narrative form, but it does in an emotional form. It leaks over from song to song — it’s not a group of songs; it’s sort of one big song.”

Unlike some singers, like Bukka White and Buddy Moss, both of whom emerged from the Southern prison system to great acclaim on the folk festival circuit, Salsburg finds Smith’s songs entirely removed from popular context. “What J.B. is using is a form that has no application outside of an occupational tradition,” Salsburg says. “Levee camps, turpentine camps, and prison farms. To me, it just goes to show that J.B. had no aspiration to release a record of this stuff. He did it purely to keep himself company, to make himself feel better, to express himself. That’s deeply moving to me.”

Smith was paroled in 1967, and Jackson, who was director of the Newport Folk Festival, arranged for him to appear there with Pete Seeger. After that, he went to Amarillo, where his oratory skills were put to good use as a preacher. A parole violation sent him back to prison, and Jackson never heard from him again. But, “When I listen to it, I remember exactly where we were,” Jackson says. “It all comes flooding back.”

As an art form, prison songs are gone, and as Salsburg writes in his introduction, “it’s hard to mourn their extinction. Many of them arose from social, economic, and political arrangements that deserved to die. The iniquities of the turpentine, lumber, and leave camps; the injustices of the sharecropping system. Slavery itself.”

Yet, what Jackson and other field recorders captured in those hellish places remains culturally significant.

“They were an important expression of what people were thinking and feeling,” Jackson says. “Prison work songs originated in Africa; they came to the slave plantations where they were used in exactly the way they were used in the prisons. The prisons, many of them, were built on locations that had been slave plantations. The convicts worked under conditions very much like the slaves and they used songs in very much the same way. Had we not recorded them, they would have simply disappeared from the face of the earth. That important part of history would be unknown to us and future generations.”