here is the NFO file from Indietorrents

———————————————————————

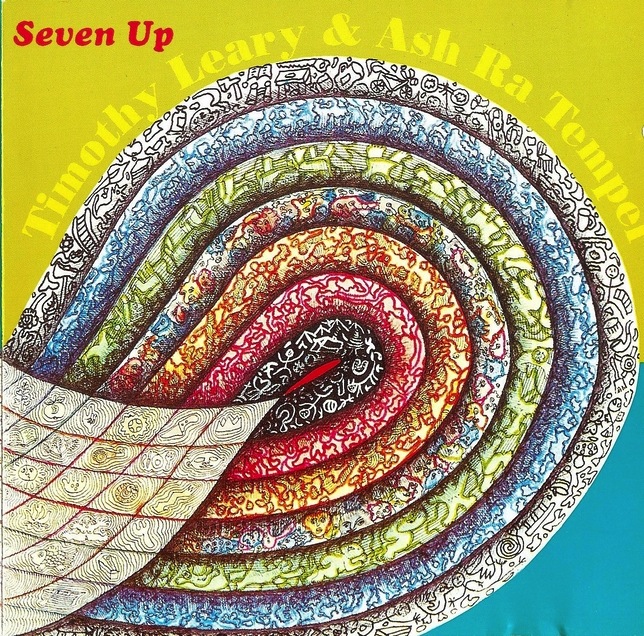

Ash Ra Tempel with Timothy Leary – Seven Up

———————————————————————

Artist……………: Ash Ra Tempel with Timothy Leary

Album…………….: Seven Up

Genre…………….: Psychedelic Rock

Source……………: NMR

Year……………..: 1972

Ripper……………: NMR

Codec…………….: LAME 3.99

Version…………..: MPEG 1 Layer III

Quality…………..: Extreme, (avg. bitrate: 248kbps)

Channels………….: Joint Stereo / 44100 hz

Tags……………..: ID3 v1.1, ID3 v2.3

Information……….:

Ripped by…………: NMR

Posted by…………: somebody on 18/03/2013

News Server……….:

News Group(s)……..:

Included………….: NFO

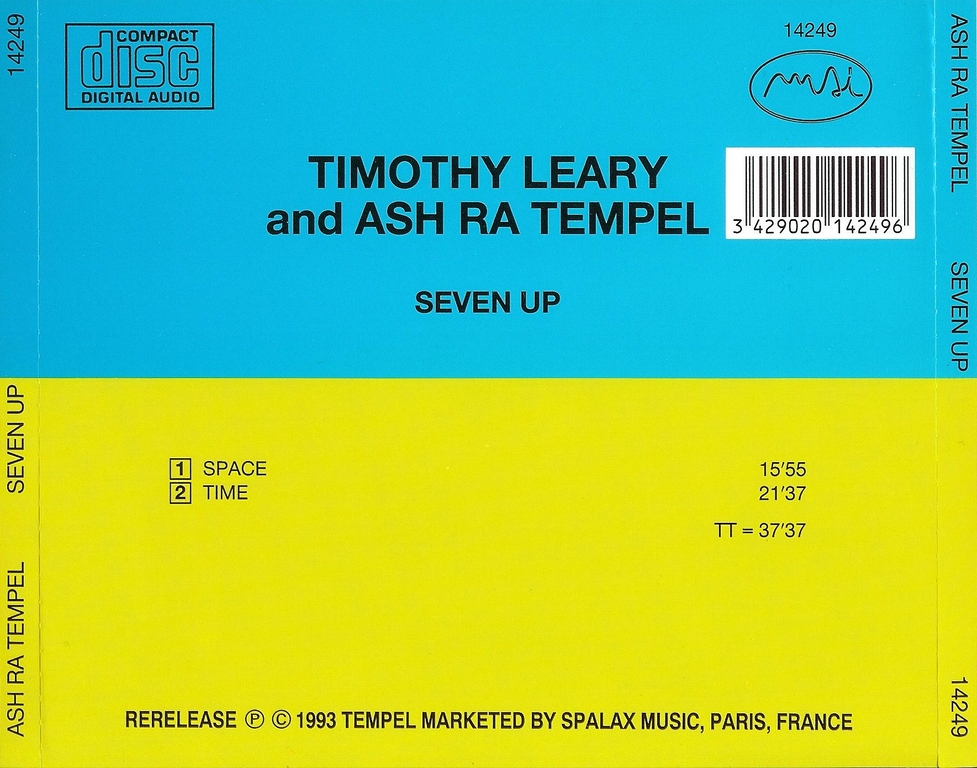

Covers……………: Front Back CD

———————————————————————

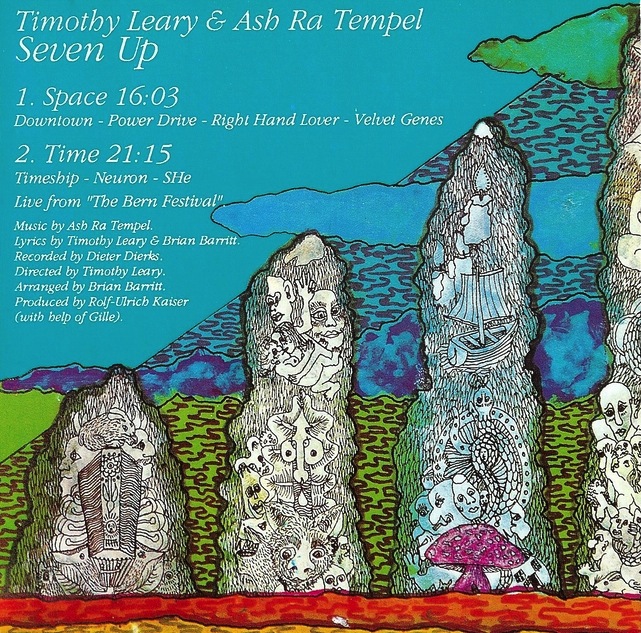

Tracklisting

———————————————————————

1. Ash Ra Tempel with Timothy Leary – Space [16:00]

2. Ash Ra Tempel with Timothy Leary – Time [21:36]

Playing Time………: 37:37

Total Size………..: 67.61 MB

NFO generated on…..: 18/03/2013 02:43:20

:: Generated by Music NFO Builder v1.21b – www.nfobuilder.com ::

Album info

THE MAKING OF ‘SEVEN-UP’

http://www.higgs1.demon.co.uk/barritt/mojo.htm

“On the night of September 12th 1970, Dr Timothy Leary escaped from jail…”

http://www.higgs1.demon.co.uk/barritt/mojo.htm

An edited version of this article appeared in the April 2003 edition of Mojo.

THE MAKING OF ‘SEVEN-UP’

On the night of September 12th 1970, Dr Timothy Leary escaped from jail. He climbed a tree in the exercise yard, jumped onto the roof of the cellblock, and shimmied along a telephone wire until he was over the fence. Half way along the wire his glasses fell off, and a patrol car drove underneath him, yet somehow his escape went undetected. Within days he would be flying to Algeria, with a fake passport in the name of McNellis and a bald head as his disguise. The California Men’s Colony-West at San Luis Obispo was a minimum security prison, but it was still a brave and daring escape, especially for an ex-Harvard Professor of Psychology just a few weeks shy of his 50th birthday. The authorities were shocked to find him missing; he was in the minimum security prison because his psychological profile showed a docile man who was not an escape risk. But Leary had found it easy to trick the psychological tests, as he had written them himself many years before. He was embarking on a fugitive life that would be full of glamour, excitement and danger. And, although he could never have guessed it at the time, he was going to record one of the era’s strangest and most ambitious albums: Seven-Up, with Ash Ra Tempel.

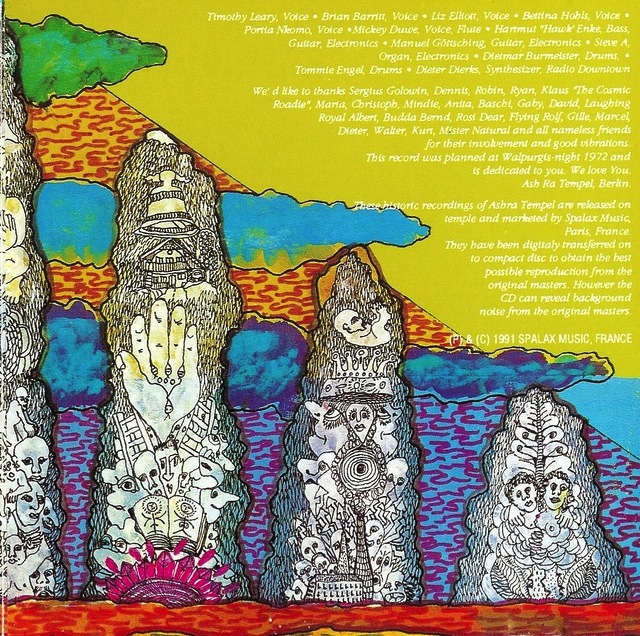

Ash Ra Tempel were formed in Berlin in 1970, thanks in part to the impressive size of Pink Floyd’s old speakers. Schoolfriends Manuel Göttsching (guitar) and Hartmut Enke (bass) had been playing together since they were 14. They called themselves the Steeplechase Blues Band, and originally covered British bands like the Beatles, Small Faces or The Who. Before long their music would evolve and they would concentrate on improvised blues instrumentals.

The Berlin music scene was tiny at the time, so when it came time to get some new equipment, Enke set off for London. Here he found four massive speakers that had previously been owned by Pink Floyd. Somehow Enke managed to single-handedly load these huge cabinets into taxis, trains and a ferry, and get them back home. “From that moment on we had the biggest equipment in Berlin!”, Göttsching remembers with evident glee.

Klaus Schulze (drums) had recently left Tangerine Dream when he stumbled into Enke and Göttsching’s rehearsal room. Upon seeing the size of their cabinets he immediately suggested that they form a band together. The three went straight to a pub and within half an hour Ash Ra Tempel was born. Schulze not only gave the trio their new name, but he introduced them to the co-owner of Ohr Recordings, Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser.

“When we started there was no audience for German groups in Germany”, Kaiser told the International Times in 1974. “The business was controlled by British and American groups. In Germany it is illegal to be a group’s manager. After three weeks [of starting Ohr] I got asked to go to the government office and they said, ‘You do something which is not allowed. If you go on you have to pay 30,000 marks fine'”. The problem was that a manager tries to find work for his band, but in Germany only the Arbeitsamt, or labour exchange, is allowed to arrange work for people. Even today a manager can only operate with special permission from the Arbeitsamt. Kaiser managed to get around this problem by going into business with Peter Meisel, who then ran Germany’s biggest music publishing company.

But it wasn’t the lengths that Kaiser went to create a music industry that made him such a revolutionary figure in German music. It was the type of music that he signed. The German bands that did exist copied English and American rock. Kaiser believed that it was possible for German musicians to create an entirely new sound of their own. “In 1970 there were no German record companies interested in German music”, he explained, “We showed the German People that they can trust their own music”.

Ash Ra Tempel had dropped the blues influences from the Steeplechase Blues Band, but they had kept the love of improvisation and experiment. They signed to Ohr and released their first, self titled LP before Schulze left the band to start a successful solo career. Schulze was eager to leave the drum kit behind and experiment with the emerging technology of synthesisers. But he remained on good terms with Göttsching and Enke, and they would collaborate again many times in the future.

Wolfgang Müller took over Schultze’s drumstool and the band recorded their second album, Schwingungen (‘vibrations’). By now it was clear that something special was happening. The music flowed from the blissful and serene to the urgent and dark. It seemed forward looking, concerned with a bright future rather than an ugly past, and it justified Kaiser’s belief in a new and original German music. English journalists would later group Ash Ra Tempel together with many varied and different German bands under the dismissive term ‘Krautrock’. But soon Kaiser found his own label for the new sound. This was Kosmische Musik, and it was the music of Paradise.

When it came to producing a follow up to Schwingungen, the band had the idea of collaborating with an American underground hero of theirs. “We wanted to make an album with Allen Ginsberg”, remembers Göttsching, “because we had some text by him on the sleeve of our first album. But Allen Ginsberg was nowhere to be found!”

Meanwhile, Leary had arrived in Switzerland, the birthplace of LSD. Switzerland is comprised of a number of semi-autonomous districts called Cantons, and as long as Leary kept moving from Canton to Canton, without staying in the one place for too long, he knew he would be safe from extradition to the United States.

To the outside world, it seemed that permanent exile in Europe could have appealed to Leary. “In Europe we have been contacted by several elitist, aristocratic, thoughtfully decadent drug taking groups of older people”, he told Oz magazine in 1972, “who follow traditions which trace back through French poets, German mystics, elegant hashishines, silk-satin opium adepts. It’s a deep, wise old continent and quite together at the moment”. In these circles, Professor Leary was no longer seen as the evil destroyer of children that the American media described. He was surprised to find himself respected, and was offered teaching positions in Swiss Universities. His life appeared to be successful and exciting. He had just sold a book, Confessions of a Hope Fiend, to Bantam for $250,000, and had bought a bright yellow Porsche. He unofficially ‘married’ a number of women, in personal ceremonies involving gold rings. “The only graces lacking here”, he commented, “are Mexican grass and Californian girls”.

But behind his public face and his famous smile, things were a little more difficult. His adventures on the run were starting to take their toll. Leary had had to escape from Algiers after his initial sanctuary from American law, the Black Panthers’ Algerian Embassy, had turned into another prison. He felt frustrated because he longed to return to his American homeland, and in these circumstances even Switzerland started to feel like yet another jail. Financially, he had lost the majority of the book money to an exiled French arms dealer called Michel Hauchard. More importantly, his wife Rosemary had left him shortly after they arrived in Switzerland. In his 1971 Swiss diary, he makes a number of references to being depressed.

A big influence on him at this time was the English author Brian Barritt. Like Leary, Barritt was no stranger to psychedelics, jail, or adventure. They had met in Algiers the year before and, when Leary got writer’s block trying to finish his book, he asked Barritt to fly to Switzerland and help. Barritt helped steer Leary away from science and towards art, mysticism and the occult. Like most men when they’re marriages break up, Leary went a little crazy for a while. They experimented with heroin, and both have claimed that they were communicating telepathically at the time.

Having failed to locate Ginsberg, Kaiser was thrilled to learn that the great Dr Leary was now over the border in Switzerland. Enke went to meet him to discuss collaboration, and gave him a copy of Schwingungen. “We hadn’t heard of Ash Ra Tempel at the time”, Barritt explains. “But we had been listening to odds and sods of German music. And we liked it. They weren’t trying to be popstars or anything like that, they didn’t really have any pop star traditions. They were more like a crowd of people who liked playing music who got together and studied music and could make good music. It sounded great to us because we’d got tired of Pink Floyd, and the stuff we were getting from the States and England was pretty sort of low-key compared to the lifestyle we were living”.

Leary and Barritt had been working together on a new description of consciousness, and they suggested making an album about the different states that they had been experiencing. Of course, they were hardly the first people to talk about these states. Artists, saints and madmen have recorded them throughout history. But thanks to LSD they were no longer limited to only sporadic and unpredictable access to them. They now had a vehicle with which they could travel to them whenever they wished.

Leary and Barritt saw themselves as revolutionary explorers in the Brave New World of Inner Space, and they thought that they shared the same duty as the real-world explorers before them. They had to bring back a map. Their ‘mind map’ divided consciousness into 7 separate stages or levels, through which it was possible to rise. The first four levels are uncontroversial, and deal with awareness of attraction, power, social positions and sex. These stages in a child’s development will take them from birth to adolescence.

The next three levels are a little trickier. These are the states that scientists are uncomfortable with, as there seems little reason for them to evolve naturally. They are concerned with an artistic appreciation of beauty, a profound sense of connection with the cosmos, and finally an understanding or archetypes and genetic history caused by stepping outside the regular flow of time. It is impossible to get any ‘higher’ than this, they argued, because you then loose your ego or any concept of self. You cannot go higher because there would no longer be any ‘you’ left. This is the ‘white light’, a state that Barritt had glimpsed once but Leary never achieved.

Leary’s idea was to make a record that would be a musical interpretation of this mind map system. Side one, which was called ‘Space’, would feature songs based on the four lower levels. Side two, ‘Time’, would be three instrumentals based on the three higher levels. This was described by Barritt with the equation, “Time + Space = timESPace”. Put the Time and Space sides of the record together, he said, and the ESP would appear in the hole in the centre.

We can only guess what Enke’s initial reaction to all this extreme talk was. He was talented and driven, but he was young. Like Göttsching, he was still at school at the time. Hearing all these theories from such a charismatic and infamous man as Leary clearly had a profound effect, and he was soon totally convinced. A meeting to sign a contract for the album was arranged in the Juker Café in Berne, where Tim sat in the same chair once used by Albert Einstein. While Schwingungen was very much Göttsching’s project, Enke would become the driving force of the new album. He headed back to Germany and got to work.

Enke recruited a whole bunch of new musicians into Ash Ra Tempel. They were mostly young, inexperienced amateurs, but they bulked up the band’s sound into a fluctuating group of between five or seven musicians. Together they went into the studio and worked out the seven basic tracks (the tapes of these sessions are still filed away in Göttsching’s archive). For the first couple of songs, the lowest levels, they drew on their experience of their days as the Steeplechase Blues Band and produced blues workouts. For the final and ‘highest’ track, they reworked the climax of side two of Scwingungen, Suche & Liebe, as it seemed unlikely that they could write a more fitting or transcendent piece of music. Leary couldn’t travel to Berlin without risking capture, so the band had to go to him. Klaus D. Mueller, who was then Ash Ra Tempel’s roadie and is now Klaus Schulze’s publisher, borrowed a Revox tape recorder from Schulze, and the musicians set off for Switzerland.

They stayed for a week in a big house in the mountains near Berne, which belonged to a friend of Leary’s called Albert Mindy. It was an idyllic, peaceful setting and there was a constant influx of many friends and visitors. Leary made a great impression on the young German musicians. “He was very friendly, always laughing”, remembers Mueller. “For me he was not ‘one of us’, but more an adored guru, kind of untouchable. Had maybe to do with the fact that he could be our father, age-wise”.

“I’d never heard of Tim Leary before”, admits Göttsching. “I didn’t know who he was! But I was a bit afraid because of the stories Hartmut told me. In the end he was a very nice guy, a very American guy, and very open minded. I expected something like an Indian guru, with lots of hair and chanting. He managed very well to get along with all those different characters in the group. He could sit with some people and drink a beer, he could smoke a joint, he could talk with everybody in a different way, so he was very flexible”.

Although some people deny this, it seems certain that at least one orgy took place at the time, as Leary mentions it in his notes. It seems likely, however, that most of the Ash Ra Tempel party were not involved. It was initiated by Brian Barritt. “I remember that there was a lot of legs!” he says. “Ten people or something like that, all fucking at random, moving on to one another, all out of our skulls. I got the blame for that…”

Recording took place in Sinus Studios, Berne, over three hot days and nights in August 1972. This was a small, underground studio. It was entered by wooden shutters in the pavement above, which gave the impression of entering a crypt. Things got off to a good start when Leary’s son-in-law, Dennis Martino, spiked a bottle of 7-Up with some crystal acid and, without informing the band, passed it round. Whatever the ethics of his actions, this did allow Barritt to finally stumble upon the perfect name for the album: ‘Seven-Up’.

The first day was spent sorting out technical problems with the equipment, while Leary and Barritt got to work on the lyrics. They filled page after page of A4 with stream-of-consciousness notes, thoughts and ideas. These pages, hand-written either in biro or one of a number of psychedelically coloured felt tips, still exist and show the gradual evolution of the songs from abstract concepts into finished lyrics. The tracks on side one were recorded the next day, and side two was recorded on the final day.

It was a surprise for the band when they saw Leary walk up to the microphone. “It was not intended that Tim was going to sing”, says Göttsching, “we’d never talked about it before. In the beginning the idea was just that he speaks, or that our singers would sing his words. But then he just started to sing! He was a good singer. Better than ours!”

The album was mixed by Dieter Dierks at his studio just outside Cologne. As Leary couldn’t risk travelling to Germany, he sent Barritt along to oversee the mix. When they played the tapes back they discovered that the first track was almost blank, and had to be re-recorded. A local singer, Portia Nkomo, was brought in to record the vocal. “While she was singing I said dirty things to her over the headphones, you know, to try and make her freak out,” recalls Barritt. “But she didn’t. She was much too professional.”

The atmosphere for the mix was relaxed and improvised. “Brian Barritt was sitting there, calling Timothy in Switzerland and playing the music to him through phone”, remembers Göttsching, “and he’d record some of Tim’s voice long distance and add it to the record. That was fun.” At one point Dierks had the studio rigged as a radio station, and anyone local who tuned their radios in would hear ‘Seven-Up’ blasting out.

With so many people involved, it was inevitable that the mix would be a bit of a compromise. The four tracks on side one were merged together into one long piece, and Dierks added washes of synthesisers to blur the joins. “I didn’t like the synthesiser thing on the first side, but Tim liked it very much”, says Göttsching. But Leary wasn’t getting everything his own way. “We wanted them to cut the song ‘Downtown’ in half, because it goes on much too long”, says Barritt. “But I didn’t have absolute power. Kaiser had absolute power”. Leary was not happy with Kaiser’s control of the project. “After the sessions in Berne were finished”, remembers Barritt, “Tim said, ‘Get over to cologne as fast as you can, before Kaiser fucks about with it’. So I shot over to Cologne, you know, and he’d already fucked about with it”.

But although Leary had minor complaints about the finished record, he was excited by the overall result. “Tim was proud of his work on Seven-Up”, recalls Michael Horowitz, Leary’s friend and archivist who visited him shortly after the record was finished. “It was an exhilarating experience for him. He had already cut quite a few albums but this was the first time he worked with a band, and vocalised”. His belief in the record is also demonstrated by the fact that he sent a tape of it to the Moody Blues.

‘Seven-Up’ is a difficult album to love musically. The range of styles involved is huge. Some parts are ambient and serene, yet elsewhere it sounds like punk, which is quite an achievement for 1972. This does mean, however, that its overall personality is very schizophrenic. Those involved speak of the great time they had recording it, or their intellectual satisfaction with what they got across, but no-one claims that they still listen to it. Barritt says that it is only suitable for listening to in the 45 minutes between dropping a tab of acid and the drug kicking in, just as you’d look at a road map before a car journey to give you an idea of where you were headed. But it terms of it’s ambition, and the circumstances of it’s creation, then it is hard to deny that Seven-Up is a remarkable record. In many ways it represents the pinnacle of sixties idealism. Kaiser, Enke and Leary believed that it was possible to make a record that, if not quite intended to take you to Heaven, would at least serve as a map to the car park next to the Pearly Gates. It is hard to imagine any contemporary artists operating at the same level of arrogance and ambition. Musicians may never get quite that high again.

Things went downhill quickly for most of the people involved in Seven-Up. Leary was finally arrested in Kabul airport, Afghanistan, a few months after the record was finished. He spent the next few years in an American jail. Kaiser would later be sued by his own musicians, after failing to pay them and using recordings without permission. His increasingly erratic behaviour and financial problems would finish him in the German music business that he helped create, and he disappeared in the late seventies. “Over the years I’ve heard some rumours about his whereabouts”, says Göttsching. “Some say that he lives in Australia, one said that he had seen him in Bavaria”. But nobody knows for sure.

Enke would soon leave the music business after suffering some form of mental problem, which many believe was linked to LSD. “During our last concert in Cologne in February ’73”, remembers Göttsching. “Hartmut stopped playing bass in the middle of the concert and just sat down on the stage. Klaus and me we looked at each other, and we continued to play, thinking maybe he wanted a break. And after the concert we asked him, ‘Hartmut, what happened?’ and then he said, ‘yeah, the music that you played was just so beautiful I didn’t know what to play. I preferred to listen to it’.” He left the band shortly afterwards. He still lives in Berlin and Göttsching sees him regularly, but no-one expects him to perform professionally again.

Göttsching, however, has continued to record. He recruited new musicians and formed a new band called Ashra. He also records as a solo artist, and his hugely influential 1984 album ‘E2-E4’ has earned him the nickname ‘The Godfather of Trance’. He is currently the subject of a film called ‘Killing Manuel’. Brian Barritt now lives in South London, where he writes obscene short stories and shows no sign of settling into respectable retirement.

Musically, Leary was more at home with American or British artists. His great loves were Billie Holiday, Miles Davis and the Rolling Stones. He skipped over the making of this record in his autobiography, and he rarely mentioned it to his American friends. But it is clear that there was something about Kosmische music, or the recording of Seven-Up, that never left him. When Barritt visited him before he died he found him listening to Manuel Göttsching. “Well Brian”, he said, referring to the music, “We landed in the right place at the right time…”