Early life

Billie Holiday had a difficult childhood, which greatly affected her life and career. Much of her childhood is clouded by conjecture and legend, some of it propagated by her autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, published in 1956. This account is known to contain many inaccuracies.

Her professional pseudonym was taken from Billie Dove, an actress she admired, and Clarence Holiday, her probable father. At the outset of her career, she spelled her last name “Halliday,” presumably to distance herself from her neglectful father, but eventually changed it back to “Holiday.”

There is some controversy regarding Holiday’s paternity, stemming from a copy of her birth certificate in the Baltimore archives that lists the father as a “Frank DeViese”. Some historians consider this an anomaly, probably inserted by a hospital or government worker.

Thrown out of her parents’ home in Baltimore, Billie’s mother, Sadie Fagan, moved to Philadelphia where Billie was born. Mother and child eventually settled in a poor section of Baltimore. Her parents married when she was three, but they soon divorced, leaving her to be raised largely by her mother and other relatives. At the age of 10, she reported that she had been raped. That claim, combined with her frequent truancy, resulted in her being sent to The House of the Good Shepherd, a Catholic reform school, in 1925. It was only through the assistance of a family friend that she was released two years later. Scarred by these experiences, Holiday moved to New York City with her mother in 1928. In 1929 Holiday’s mother discovered a neighbor, Wilbert Rich, in the act of raping her daughter; Rich was sentenced to three months in jail.

Early singing career

According to Billie Holiday’s own account, she was recruited by a brothel, worked as a prostitute in 1930, and was eventually imprisoned for a short time for solicitation. It was in Harlem in the early 1930s that she started singing for tips in various night clubs. According to legend, penniless and facing eviction, she sang “Travelin All Alone” in a local club and reduced the audience to tears. She later worked at various clubs for tips, ultimately landing at Pod’s and Jerry’s, a well known Harlem jazz club. Her early work history is hard to verify, though accounts say she was working at a club named Monette’s in 1933 when she was discovered by talent scout John Hammond.

Hammond arranged for Holiday to make her recording debut on a 1933 Benny Goodman date, and Goodman was also on hand in 1935, when she continued her recording career with a group led by pianist Teddy Wilson. Their first collaboration included “What A Little Moonlight Can Do” and “Miss Brown To You”, which helped to establish Billie Holiday as a major vocalist. She began recording under her own name a year later, producing a series of extraordinary performances with groups comprising the Swing Era’s finest musicians.

Wilson was signed to Brunswick by John Hammond for the purpose of recording current pop tunes in the new Swing style for the growing jukebox trade. They were given free rein to improvise the material. Holiday’s amazing method of improvising the melody line to fit the emotion was revolutionary (Wilson and Holiday took pedestrian pop tunes like “Twenty Four Hours A Day” or “Yankee Doodle Never Went To Town” and turn them into jazz classics with their arrangements). With few exceptions, the recordings she made with Wilson or under her own name during the 1930’s and early 1940’s are regarded as important parts of the jazz vocal library.

Among the musicians who accompanied her frequently was tenor saxophonist Lester Young, who had been a boarder at her mother’s house in 1934 and with whom she had a special rapport. “Well, I think you can hear that on some of the old records, you know. Some time I’d sit down and listen to ’em myself, and it sound like two of the same voices, if you don’t be careful, you know, or the same mind, or something like that.” Young nicknamed her “Lady Day” and she, in turn, dubbed him “Prez.” In the late 1930s, she also had brief stints as a big band vocalist with Count Basie (1937) and Artie Shaw (1938). The latter association placed her among the first black women to work with a white orchestra, an arrangement that went against the temper of the times.

The Commodore Years and “Strange Fruit”

Holiday was recording for Columbia in the late 1930s when she was introduced to “Strange Fruit,” a song based on a poem about lynching written by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher from the Bronx. Meeropol used the pseudonym “Lewis Allan” for the poem, which was set to music and performed at teachers’ union meetings. It was eventually heard by Barney Josephson, proprietor of Café Society, an integrated nightclub in Greenwich Village, who introduced it to Holiday. She performed it at the club in 1939, with some trepidation, fearing possible retaliation. Holiday later said that the imagery in “Strange Fruit” reminded her of her father’s death, and that this played a role in her persistence to perform it. In a 1958 interview, she also bemoaned the fact that many people did not grasp the song’s message: “They’ll ask me to ‘sing that sexy song about the people swinging’,” she said.

When her producers at Columbia found the subject matter too sensitive, Commodore Records’ Milt Gabler agreed to record it for his label. That was done in April, 1939 and “Strange Fruit” remained in her repertoire for twenty years. She later recorded it again for Verve. While the Commodore release did not get airplay, the controversial song sold well, but Gabler attributes that mostly to the record’s other side, “Fine and Mellow,” which was a juke box hit.[10]

Decca Records and “Lover Man”

In addition to owning Commodore Records, Milt Gabler was an A&R man for Decca Records, and he signed Holiday to the label in 1944. Her first recording for Decca, “Lover Man,” was a song written especially for her by Jimmy Davis, Roger “Ram” Ramirez, and Jimmy Sherman. Although its lyrics describe a woman who has never known love (“I long to try something I never had”), its themea woman longing for a missing loverand its refrain, “Lover man, oh, where can you be?”, struck a chord in wartime America and the record became one of her biggest hits.

Holiday continued to record for Decca until 1950, including sessions with the Duke Ellington and Count Basie orchestras, and two duets with Louis Armstrong. Holiday’s Decca recordings featured big bands and, sometimes, strings, contrasting her intimate small group Columbia accompaniments. Some of the songs from her Decca repertoire became signatures, including “Don’t Explain” and “Good Morning Heartache”.

Film

Holiday made one major film appearance, opposite Louis Armstrong in New Orleans (1947). The musical drama featured Holiday singing with Armstrong and his band and was directed by Arthur Lubin.

Later life

Her personal life was as turbulent as the songs she sang. Holiday stated that she began using hard drugs in the early 1940s. She married trombonist Jimmy Monroe on August 25, 1941. While still married to Monroe, she took up with trumpeter Joe Guy, her drug dealer, as his common law wife. She finally divorced Monroe in 1947, and also split with Guy. In 1947 she was jailed on drug charges and served eight months at the Alderson Federal Correctional Institution for Women in West Virginia. Her New York City Cabaret Card was subsequently revoked, which kept her from working in clubs there for the remaining 12 years of her life, except when she played at the Ebony Club in 1948, where she opened under the permission of John Levy.

By the 1950s, Holiday’s drug abuse, drinking, and relations with abusive men led to deteriorating health. As evidenced by her later recordings, Holiday’s voice coarsened and did not project the vibrance it once had.[citation needed] However, she had retained and, perhaps, strengthened the emotional impact of her delivery.[citation needed]

On March 28, 1952, Holiday married Louis McKay, a mafia enforcer. McKay, like most of the men in her life, was abusive, but he did try to get her off drugs. They were separated at the time of her death, but McKay had plans to start a chain of Billie Holiday vocal studios, a la the Arthur Murray dance schools. Holiday also had a relationship with Orson Welles.

Her late recordings on Verve constitute about a third of her commercial recorded legacy and are as well remembered as her earlier work for the Columbia, Commodore and Decca labels. In later years her voice became more fragile, but it never lost the edge that had always made it so distinctive. On November 10, 1956, she performed before a packed audience at Carnegie Hall, a major accomplishment for any artist, especially a black artist of the segregated period of American history. Her performance of “Fine And Mellow” on CBS’s The Sound of Jazz program is memorable for her interplay with her long-time friend Lester Young; both were less than two years from death.

Holiday first toured Europe in 1954, as part of a Leonard Feather package that also included Buddy DeFranco and Red Norvo. When she returned, almost five years later, she made one of her last television appearances for Granada’s “Chelsea at Nine,” in London. Her final studio recordings were made for MGM in 1959, with lush backing from Ray Ellis and his Orchestra, who had also accompanied her on Columbia’s Lady in Satin album the previous year see below). The MGM sessions were released posthumously on a self-titled album, later re-titled and re-released as Last Recordings. Her final public appearance, a benefit concert at the Phoenix Theater in New York’s Greenwich Village, took place on May 25, 1959. According to the evening’s masters of ceremony, jazz critic Leonard Feather and TV host Steve Allen, she was only able to make it through two songs, one of which was “Ain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do.”

On May 31, 1959, she was taken to Metropolitan Hospital in New York suffering from liver and heart disease. On July 12, she was placed under house arrest at the hospital for possession, despite evidence suggesting the drugs may have been planted on her. Holiday remained under police guard at the hospital until she died from cirrhosis of the liver on July 17 1959 at the age of 44. In the final years of her life, she had been progressively swindled out of her earnings, and she died with only $0.70 in the bank and $750 (a tabloid fee) on her person.

Billie Holiday is interred in Saint Raymond’s Cemetery, The Bronx, New York.

—————————————————————————————————————————

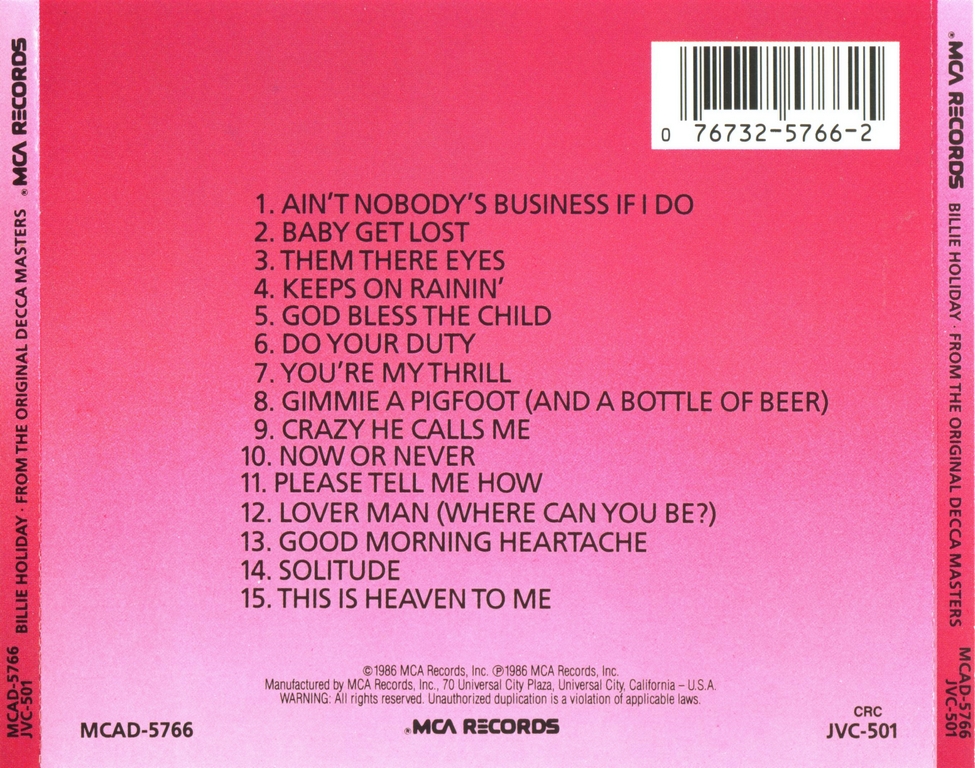

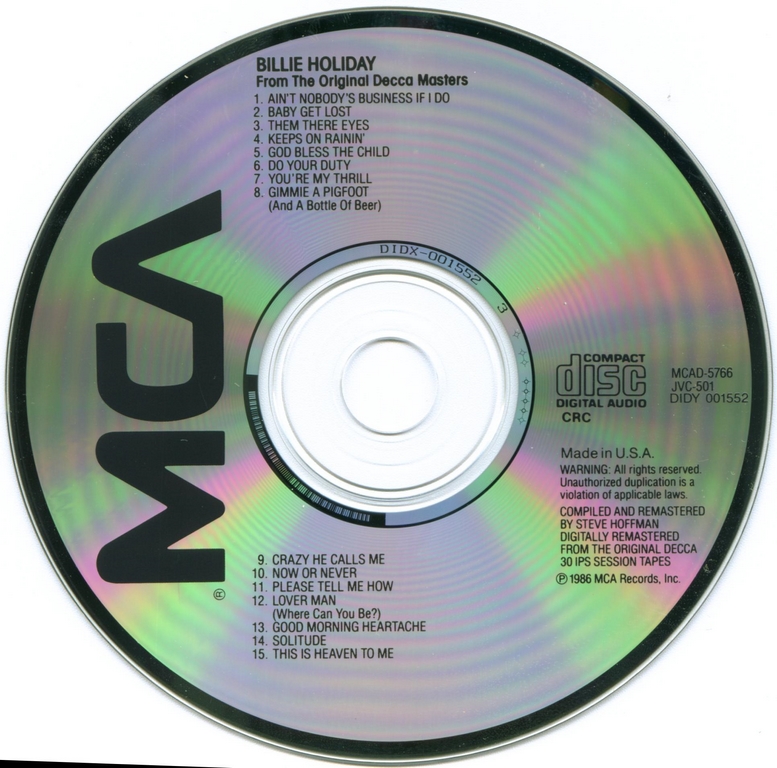

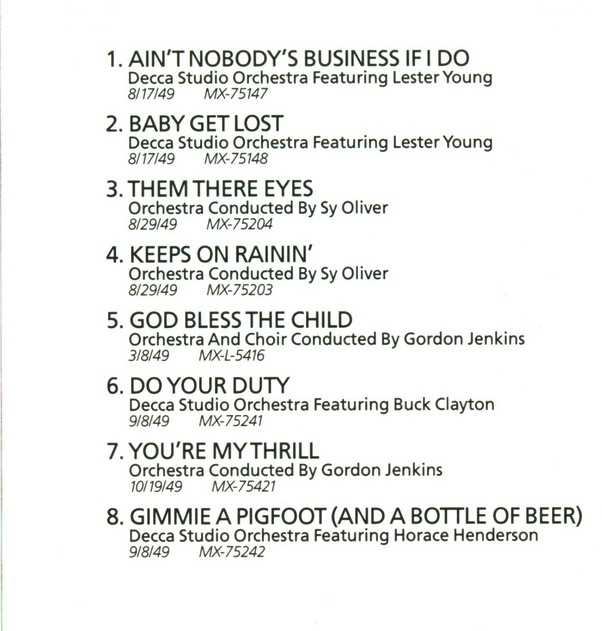

Track Listings

1. Ain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do

2. Baby Get Lost

3. Them There Eyes

4. Keeps on Rainin’

5. God Bless the Child

6. Do Your Duty

7. You’re My Thrill

8. Gimmie a Pigfoot (And a Bottle of Beer)

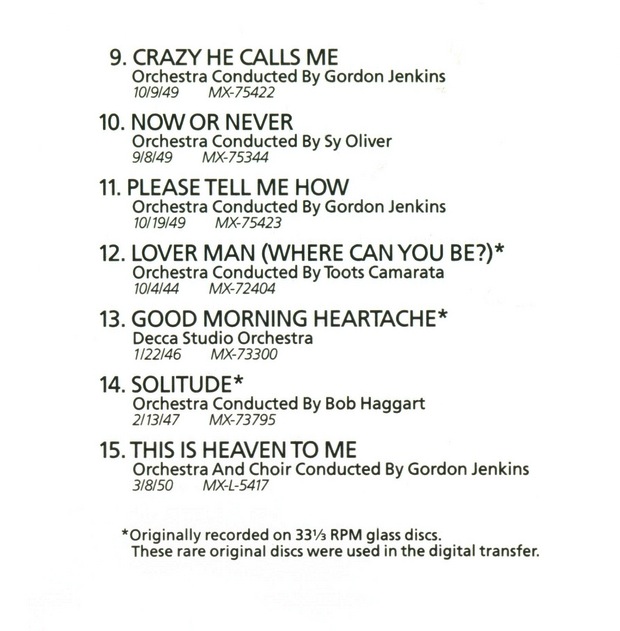

9. Crazy He Calls Me

10. Now or Never

11. Please Tell Me How

12. Lover Man (Where Can He Be)

13. Good Morning Heartache

14. Solitude

15. This Is Heaven to Me