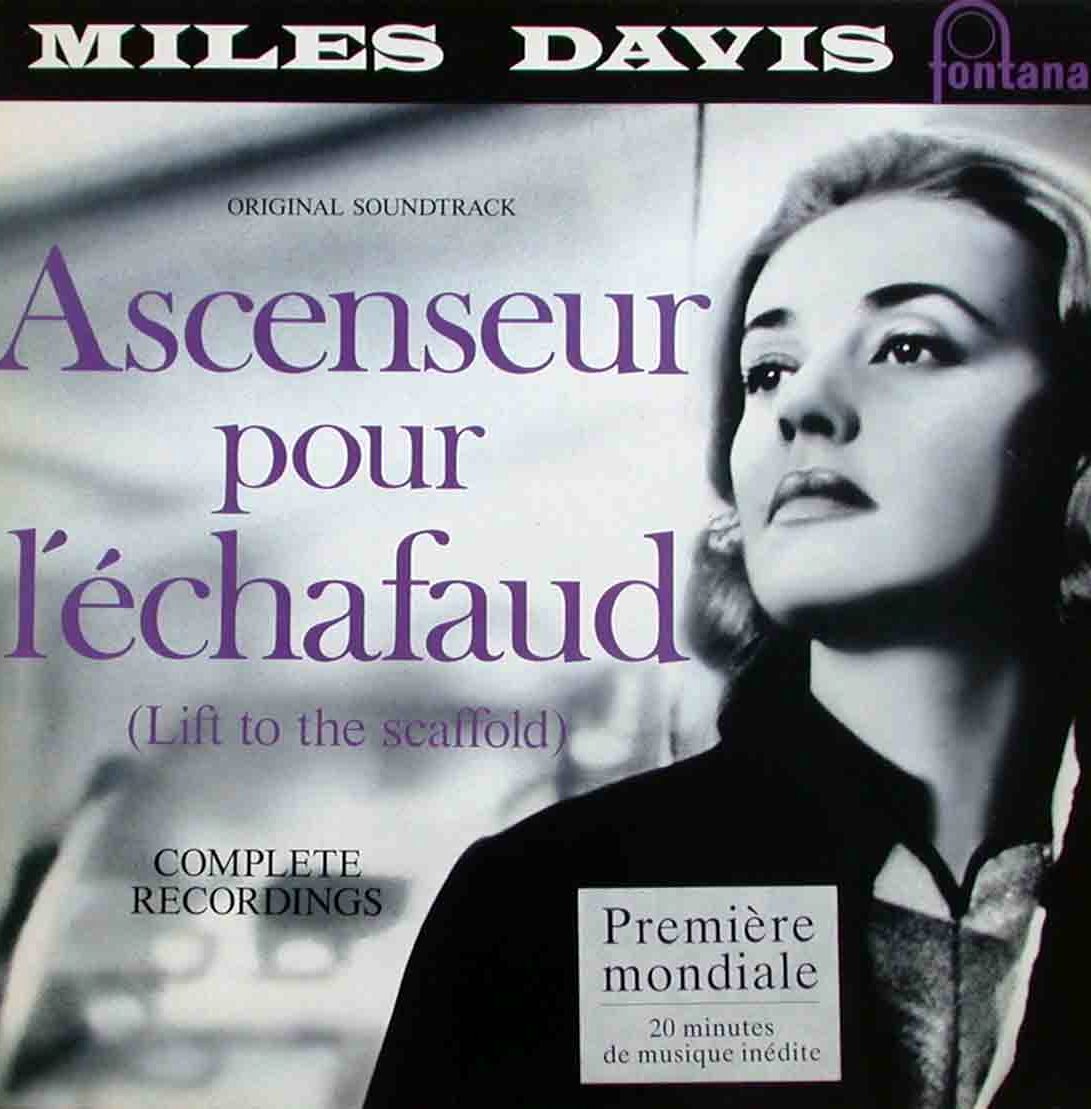

Ascenseur pour l’échafaud is an album by jazz musician Miles Davis. It was recorded at Le Poste Parisien Studio in Paris on December 4 and 5, 1957. The album features the musical cues for the 1958 Louis Malle film Ascenseur pour l’échafaud.

Jean-Paul Rappeneau, a jazz fan and Malle’s assistant at the time, suggested asking Miles Davis to create the film’s soundtrack possibly inspired by the Modern Jazz Quartet’s recording for Roger Vadim’s Sait-on jamais (Does One Ever Know), released a few months earlier in 1957.

Davis was booked to perform at the Club Saint-Germain in Paris for November 1957. Rappeneau introduced him to Malle, and Davis agreed to record the music after attending a private screening. On December 4, he brought his four sidemen to the recording studio without having had them prepare anything. Davis only gave the musicians a few rudimentary harmonic sequences he had assembled in his hotel room, and, once the plot was explained, the band improvised without any precomposed theme, while edited loops of the musically relevant film sequences were projected in the background.

Jazz Track, an album which contains the original ten songs from the soundtrack and three additional tracks later released on 1958 Miles, received a 1960 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance, Solo or Small Group.

From a musical point of view, the mood and the characteristics of the soundtrack immediately precede and introduce to Miles Davis’s masterpieces Milestones and Kind of Blue.

Miles Davis trumpet

Barney Wilen tenor saxophone

René Urtreger piano

Pierre Michelot bass

Kenny Clarke drums

review by Michael G. Nastos

Jazz and film noir are perfect bedfellows, as evidenced by the soundtrack of Louis Malle’s Ascenseur Pour L’Echafaud (Lift to the Scaffold). This dark and seductive tale is wonderfully accentuated by the late-’50s cool or bop music of Miles Davis, played with French jazzmen — bassist Pierre Michelot, pianist René Urtreger, and tenor saxophonist Barney Wilen — and American expatriate drummer Kenny Clarke. These complete recordings, including multiple alternate takes, evoke the sensual nature of a mysterious chanteuse and the contrasting scurrying rat race lifestyle of the times, when the popularity of the automobile, cigarettes, and the late-night bar scene were central figures. Davis had seen a screening of the movie prior to his making of this music, and knew exactly how to portray the smoky hazed or frantic scenes though sonic imagery, dictated by the trumpeter mainly in D-minor and C-seventh chords. Michelot is as important a figure as the trumpeter because he sets the tone, whether on four takes of the ballad/blues “Nuit sur les Champs-Élysées,” the last version a bit more swinging than the others; his probing one-note sound with the whispering horn of Davis during “Assassinat” and “Final”; and especially on his solo tracks, the slow walking “Ascenseur” (aka “Evasion de Julien”) and the stalking “Visite du Vigile.” While the mood of the soundtrack is generally dour and somber, the group collectively picks up the pace exponentially on the hard-swinging and freewheeling “Motel,” the hotter “Sequence Voiture,” and “Diner au Motel.” These selections with the entire quintet featuring Wilen effectively realize chase scenes or mind gears crazily turning. At times the distinctive Davis trumpet style is echoed into dire straits or death wish motifs, as on “Generique” or “L’Assassinat de Carala,” respectively, but the band can get kinda blue on takes of “Le Petit Bal,” with Davis and Wilen more unified up front. Clarke is his usual marvelous self, and listeners should pay close attention to the able Urtreger, by no means a virtuoso but a capable and flexible accompanist. This recording can stand proudly alongside Duke Ellington’s music from Anatomy of a Murder and the soundtrack of Play Misty for Me as great achievements of artistic excellence in fusing dramatic scenes with equally compelling modern jazz music.