BOOKLET

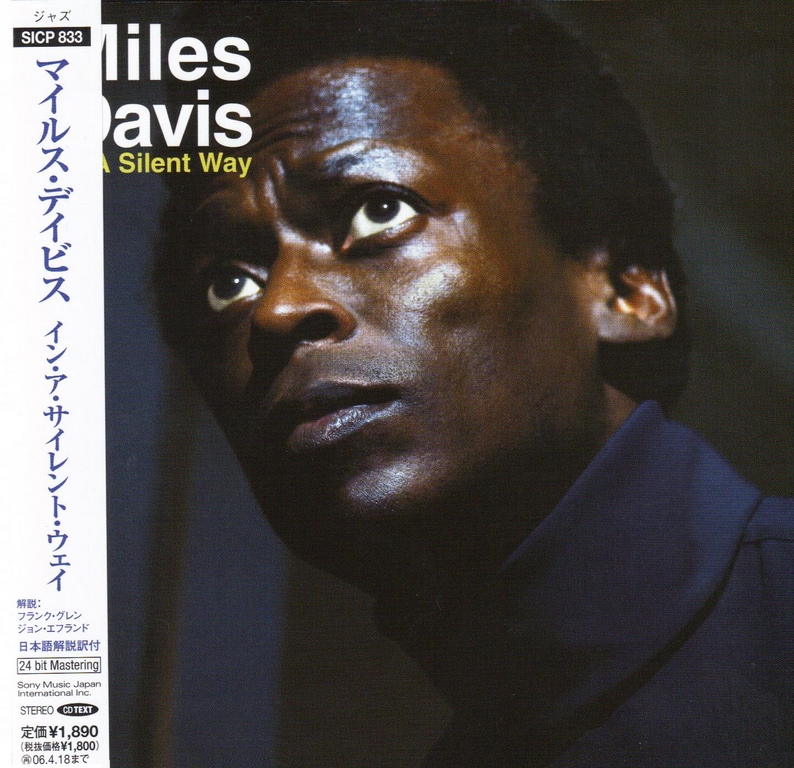

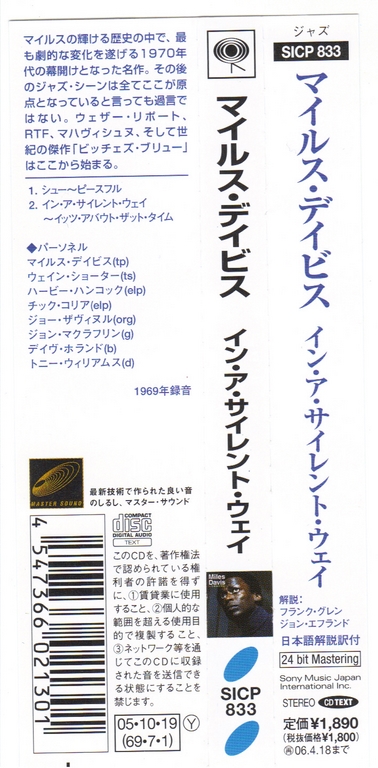

In a Silent Way is a studio album by American jazz musician Miles Davis, released July 30, 1969 on Columbia Records. Produced by Teo Macero, the album was recorded in one session date on February 18, 1969 at CBS 30th Street Studio B in New York City. Incorporating elements of classical sonata form, Macero edited and arranged Davis’s recordings from the session to produce the album. Marking the beginning of his “electric” period, In a Silent Way has been regarded by music writers as Davis’s first fusion recording, following a stylistic shift toward the genre in his previous records and live performances.

Upon its release, the album was met by controversy among music critics, particularly those of jazz and rock music, who were divided in their reaction to its experimental musical structure and Davis’s electronic approach. Since its initial reception, it has been regarded by fans and critics as one of Davis’s greatest and most influential works. In 2001, Columbia Legacy and Sony Music released the three-disc box set The Complete In a Silent Way Sessions, which includes the original album, additional tracks, and the unedited recordings used to produce In a Silent Way.

Background and recording

Although Davis’s live performances and previous records such as Miles in the Sky (1968) and Filles de Kilimanjaro (1969) had indicated his stylistic shift to fusion, In a Silent Way featured a full-blown electric approach by Davis. It has been regarded by music writers as the first of Davis’s fusion recordings, while marking the beginning of his “electric” period. It is also the first recording by Davis that was largely constructed by the editing and arrangement of producer Teo Macero. Macero’s editing techniques have incorporated elements of classical sonata form in Davis’ recordings for In a Silent Way. Both of the extended tracks on the album consist of three distinct parts that could be thought of as an exposition, development and recapitulation. The last six minutes of the first track are actually the first six minutes of the same track repeated in exactly the same form. With this “trick” the track takes on a more understandable structure.

The album featured virtuoso guitarist and newcomer John McLaughlin, who had one month prior to the February 18th In a Silent Way session recorded his classic debut album Extrapolation. At the request of Tony Williams, McLaughlin moved in early February from England to the US to play with The Tony Williams Lifetime. Williams brought McLaughlin to Davis’ house the night before the scheduled session for In a Silent Way. Davis had not heard the guitarist before, but was so impressed that he told him to show up at the studio the next day. McLaughlin would go on to great fame in the 1970s as leader of the Mahavishnu Orchestra.

According to producer Bob Belden, organist Larry Young, whom Williams had also recently hired for his Lifetime trio, was also intended to play on In a Silent Way. However, out of fear that he would lose his entire band to Davis, Williams sent Young home as soon as he arrived. Instead Joe Zawinul, who had come to the session only as the composer of the song “In a Silent Way,” ended up playing organ on the album.

Initial reaction

Peaking at number 134 on the U.S. Billboard Top LPs chart, In a Silent Way became Davis’s first album in four years, since My Funny Valentine (1965), to reach the chart. While it performed better commercially than most of Davis’s previous work, the album’s critics were divided in their reaction upon its release. Its incorporation of electronic instrumentation and experimental structure have been sources of extreme controversy among jazz critics. According to The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), Davis’s recording process and producer Teo Macero’s studio editing of individual recordings into separate tracks for the album “seemed near heretical by jazz standards”. In his book Running the Voodoo Down: The Electric Music of Miles Davis, Phil Freeman writes that rock and jazz critics at the time of the album’s release were biased in their respective genres, writing “Rock critics thought In a Silent Way sounded like rock, or at least thought Miles was nodding in their direction, and practically wet themselves with joy. Jazz critics, especially ones who didn’t listen to much rock, thought it sounded like rock too, and they reacted less favorably”. Freeman continues by expressing that both reactions were “rooted, at least partly, in the critic’s paranoia about his place in the world”, writing that rock criticism was in its early stage of existence and such critics found “reassurance” in viewing the album as having psychedelic rock elements, while jazz critics felt “betrayed” amid the genre’s decreasing popularity at the time. However, Freeman wrote that In a Silent Way was distinct from both jazz and rock styles at the time, stating:

It didn’t swing, the solos weren’t even a little bit heroic, and it had electric guitars… But though In a Silent Way wasn’t exactly jazz, it certainly wasn’t rock. It was the sound of Miles Davis and Teo Macero feeling their way down an unlit hall at three in the morning. It was the soundtrack to all the whispered conversations every creative artist has, all the time, with that doubting, taunting voice that lives in the back of your head, the one asking all the unanswerable questions.

Phil Freeman

In a rave review of the album upon its release, Rolling Stone writer Lester Bangs described In a Silent Way as “the kind of album that gives you faith in the future of music. It is not rock and roll, but it’s nothing stereotyped as jazz either. All at once, it owes almost as much to the techniques developed by rock improvisors in the last four years as to Davis’ jazz background. It is part of a transcendental new music which flushes categories away and, while using musical devices from all styles and cultures, is defined mainly by its deep emotion and unaffected originality”. Davis’ next fusion album, Bitches Brew, showed him moving even further into the area that lay between the genres of rock and jazz. The dark, fractured dissonance of Bitches Brew ultimately proved to be instrumental in its success; it far outsold In a Silent Way.

Retrospect

Since its initial reception, In a Silent Way has been regarded by fans and critics as one of Davis’s best works. In a retrospective review, Blender writer K. Leander Williams called it “a proto-ambient masterpiece”. Citing it as “one of Daviss greatest achievements”, Chip O’Brien of PopMatters viewed that producer Teo Macero’s studio editing on the album helped Davis “embrace the marriage of music and technology”. In regards to its musical significance, O’Brien wrote that In a Silent Way “transcends labels”, writing “It is neither jazz nor rock. It isnt what will eventually become known as fusion, either. It is something altogether different, something universal. There is a beautiful resignation in the sounds of this album, as if Davis is willingly letting go of what has come before, of his early years with Charlie Parker, with John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley, of his early 60s work, and is embracing the future, not only of jazz, but of music itself”. Stylus Magazine writer Nick Southall called the album “timeless” and wrote of its influence on music, stating “The fresh modes of constructing music that it presented revolutionised the jazz community, and the shifting, ethereal beauty of the actual music contained within has remained beautiful and wonderful, its echoes heard through the last 30 years, touching dance music, electronica, rock, pop, all music”. The Penguin Guide to Jazz has included In a Silent Way in its suggested “Core Collection”.

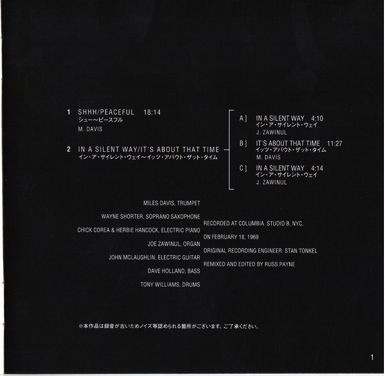

Miles Davis trumpet

Wayne Shorter soprano saxophone

John McLaughlin electric guitar

Chick Corea electric piano

Herbie Hancock electric piano

Joe Zawinul organ

Dave Holland double bass

Tony Williams drums